The White Terror is Taiwan’s collective trauma, during which countless political

prisoners were unexpectedly taken away from home and suddenly found themselves facing

seemingly unending imprisonment. Since the Japanese colonial period, Green Island had been

used for sheltering the so-called “furosha” (vagrants), and from that period on, the island

was viewed as a place for exile. It later became the prison for keeping political prisoners

during the Kuomintang regime and witnessed the violent austerity and unbearable sorrow in

the era of the White Terror.

Nonetheless, this small island off the coast of Taitung where the Black Current passes,

possesses its very own distinctive beauty—the intoxicating seascape, pristine coral beaches,

abundant plant ecology, mysterious indigenous legacies, etc. However, even though the harsh

past might appear to be buried, Green Island today faces more and new impacts, just like

many other places in the world: land development and the flourishing tourism industry, while

economically benefiting the island, lead to various collisions. As population migration in

this era of globalization introduces fresh cultural encounters, the tangible prison built in

the White Terror era is implicitly transformed into a rather intangible form of

imprisonment.

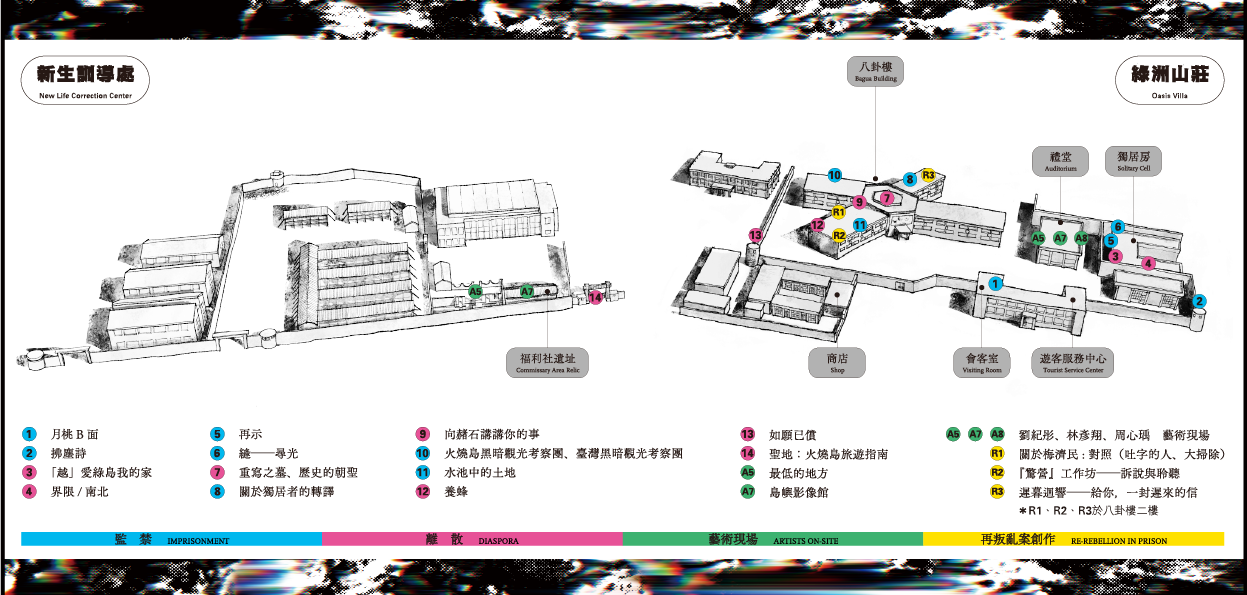

This exhibition is curated based on two themes – “imprisonment” and “diaspora” to compare

varying life circumstances in different times. Featuring diverse types of artists, including

descendants of political prisoners, new resident filmmakers, theater workers, video and

visual artists, literary writers, sound artists, etc., the exhibition presents participatory

art, non-fictional creation, island architecture, archaeology, performance art and

long-period artist residency, through which the imprisonment and memories of the White

Terror era are transformed into a mirror that reflects our modern-day experiences.

In terms of “imprisonment,” artist Huang Li-Hui, a descendant of political victims, make use

of her mother’s name “Yueh-Tao” (a homonym of the plant, shellflower) to form a connection

with shellflower stem, a common material closely linked with the life of the island’s

inhabitants, as well as her father and uncle, both were prisoned on Green Island. Huang

converts this everyday material into a metaphor for the often neglected “absent” presence of

female family members in the history of the White Terror era. Video artist Hong Jun-Yuan,

after having visited various locations on the island, decides to use the imagery of

“gap/seam” and fabricates a fictional jailbreak that eventually ends in failure based on

references to oral accounts of political prisoners. Hong’s work not only points out the

“inescapability” of the prisoners’ situation on the island but also the ubiquitous gaps and

seams that symbolize opportunities.

Moreover, Chen I-Chun, whose practice has focused on folk legends and unofficial histories,

uses her supernatural experience of “paranormal activity” on Green Island as a point of

departure to explore potential “hallucinations” that political prisoners might experience

during solitary confinement. Chen then combines this theme with related contemporary issues.

Atayal female artist Lin An-Chi specializes in performance art and draws her inspiration

from “Temahahoi,” an indigenous tribe known for the facial tattooing tradition, and its

mythology of women being impregnated by wind. Lin connects this story with the situation of

prisoners at the New Life Correction Center on Green Island during the martial law period.

Lin Chuan-Kai, on the other hand, utilizes two sites respectively on Green Island and in

Fengyuan, to cross-present how the descendants of political prisoners, who were involved in

the case of “re-rebellion” at the New Life Correction Center on Green Island, pursue and

revisit the sufferings of their elder generation. About Mei Ji-Min: Contrast (The One Who

Vomit Words, Housecleaning) by Lin Tzu-Ning and Lee Chia-Hung centers on Mei Ji-Min, a White

Terror victim and an author, and interprets Mei’s life and literary works through videos to

delineate the life circumstances of mainland Chinese political victims.

Discussing the subject of “diaspora,” Vietnamese new resident documentary filmmakers Nguyen

Kim-Hong and Tsai Tsung-Lung explore the relationship between Southeast Asian migrant

workers, Taiwan’s new residents and native inhabitants on Green Island through the story of

Vietnamese new immigrants on the island. Their project reveals the lesser known life of

foreign immigrants on Green Island. Furthermore, literary writers Wu Ke-Wei and Tsai Yu-Jou

have conducted in-depth interviews and interacted with local residents as well as visited

ruinous spaces in abandoned villages, using non-fictional writing and physical art action to

establish witty connections with and allusions to Green Island’s transformation from a place

of imprisonment to a tourist destination. Theater worker Chen Ping-Jung raises the question

of “Why are you on Green Island?” and combines a sand sieving installation with objects and

historical memories collected on the island throughout a long period of time to discuss the

meetings and partings of different economic individuals on Green Island. Visual and

conceptual artists Liao Xuan-Zhen and Huang I-Chieh base their project on an archaeological

research into architecture and co-create a coral stone house at Swallow Cave with indigenous

artists, further extending the historical dimension related to the issue of transitional

justice.

Several foreign artists are showcased in the exhibition as well: Japanese artist narco,

whose practice has revolved around investigating Taiwan’s authoritarian ruins in recent

years, adopts the approach of site-specific creation and unveils memories about the

authoritarian regime on Green Island from a non-Taiwanese perspective. Hong Kong artist Lee

Chun-Feng employs an approach mixing the real and the unreal to discuss the sensitive issue

of border awareness in Hong Kong. His work also indirectly responds to the increasingly

blurred boundaries between contemporary Hong Kong and China. Indonesian artist FX Harsono

draws his material from the history of Chinese being massacred under the Suharto regime.

Using rubbing to reveal innumerous names of victims, his work exposes a grave historical

wound outside Taiwan. In addition, a creative team from the Taipei National University of

the Arts (TNUA) also participates in the creation of the exhibition: Shih Li-Jia employs the

concept of beehives to form an interreflection between the political prisoners’ life

circumstances and that of the modern people. Xu Ming-Qian uses dust as his theme and conveys

a profound interpretation about how people were treated as dust during the authoritarian

era. With an installation resembling an operating table as well as a lightbox, Jyun-Jyue,

Lin Chih-Hong, Wan Chih-Hsuan and Liu Pei-Ling’s work departs from two similar historical

photographic images, beckoning at the complex, diverse aspects of the White Terror history.

Lastly, several artists are specially invited to carry out residencies onsite to create

“Artists on-site” in this curatorial project and produce participatory works in the

exhibition. Lin Yan-Xiang, an expert in photography-related topics, hopes to re-create the

darkroom once existed at the New Life Correction Center, and will station onsite to run a

“photography studio” to offer new connections for locals as well as tourists on Green

Island. Liu Chi-Tung, through interweaving narratives, brings together the “Liumagou

Swimming Pool” on Green Island and Yang Kui’s “Tunghai Garden” on the island of Taiwan, and

initiates an art action to gather participants to revisit the sites and reflect on the past

and present of the White Terror history. In addition, sound artist Chou Hsin-Yu will lead

participants to experience Green Island’s soundscape through auditory and physical

interaction during her residency on the island.